June 12, 2019 IN: Press Room

SEARAC, AAPI Organizations Join Together to Say No to Public Charge

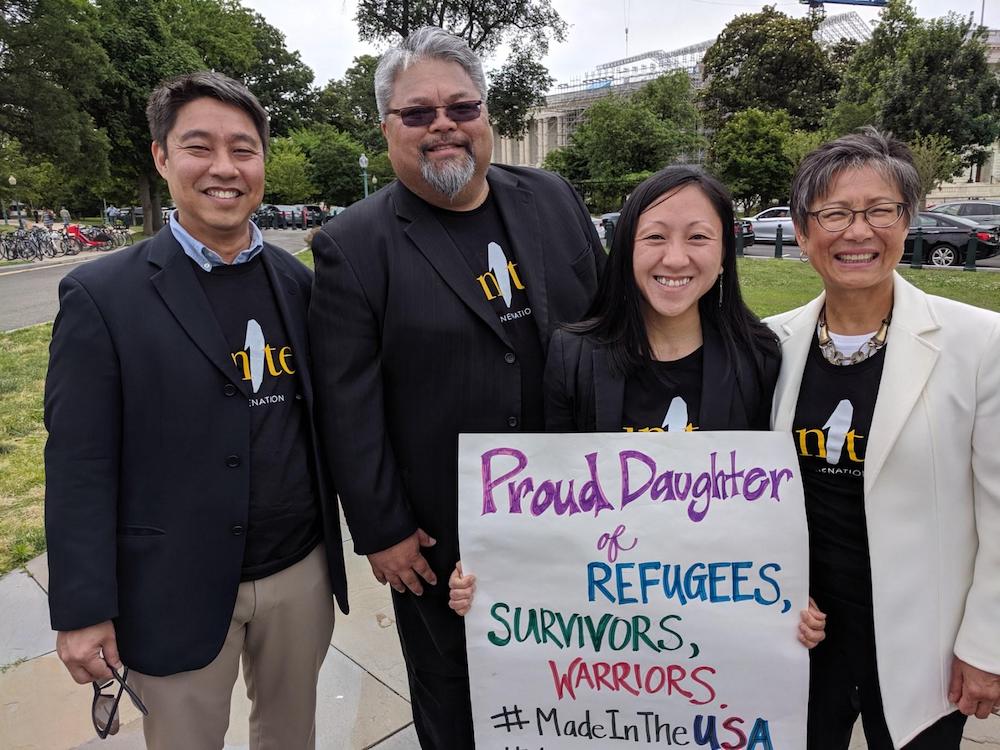

Washington, DC– SEARAC today joined our fellow partners in the One Nation Commission in front of Capitol Hill to speak out against the Trump Administration’s inhumane and un-American proposed public charge rule.

The public charge test is used to determine if a person seeking admission to the United States or wanting to obtain a green card while in the country is likely to rely on government services for support. The test is based on a number of factors, including use of public cash assistance. Under the Trump Administration’s proposed new definition, public charge determination would be expanded to include a number of additional government benefits, such as Medicaid, SNAP, Medicare Part D, and Section 8 housing assistance. As a result, the proposed change particularly impacts low-income Southeast Asian Americans who arrived to the United States through the family visa program, as these community members may feel the need to make the impossible decision of protecting their immigration status or getting the assistance they need to thrive in the United States.

The rule dismisses the fact that public services allow many families to make the American Dream a tangible reality. “Sometimes it’s forgotten that folks within the Southeast Asian American community did depend on public programs in order to establish their families,” says Hatefas Yop, former SEARAC 2018 Leadership and Advocacy Training participant and a community advocate based in California. “In my perspective, public charge further silences the big economic disparity we face. It further silences the struggle to reunite families-and we have to remember why our families need to be reunited.”

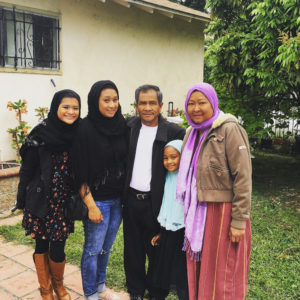

Born in Santa Ana, CA, to two Muslim refugee survivors of the Cambodian genocide, Hatefas wasn’t aware of her family’s use of public services when she was a young girl. After all, her peers in her elementary school all hailed from the local neighborhood, where many immigrant and refugee families had to live in one-bedroom apartments subsidized by Section 8 housing. In middle school, Hatefas noticed that her life was different from the students from other demographics and income brackets. She realized she had reduced lunch, and that going to the doctor only happened when something was extremely concerning or severe. “Access to healthcare was something completely foreign,” she says. “We didn’t grow up having regular doctor routines.”

What Hatefas hopes for most of all is empathy. “Community members who are eligible for these programs need the help. By penalizing them for using these services, it puts into their minds that every small encounter can possibly jeopardize their life in America,” she says.

Click here to read our latest community story, Hatefas’ Story: Public Assistance Allowed My Refugee Family to Dream for a Better Future.

Click here to read our latest community story, Hatefas’ Story: Public Assistance Allowed My Refugee Family to Dream for a Better Future.