March 30, 2021 IN: Community Stories

Stories from The Cambodian Family: Southeast Asian American Mental Health in CA

Since she left Cambodia, Thary Sok has resided for six years in the city of Santa Ana, CA, with a population of around 7,000 Cambodian Americans, according to the 2010 Census. Like many Cambodians, Thary’s household is a multigenerational one, with her husband, daughter, and two grandchildren living under one roof. And like 38% of Cambodian Americans, Thary is limited English proficient (LEP), which made it difficult for her to communicate her health needs with healthcare professionals.

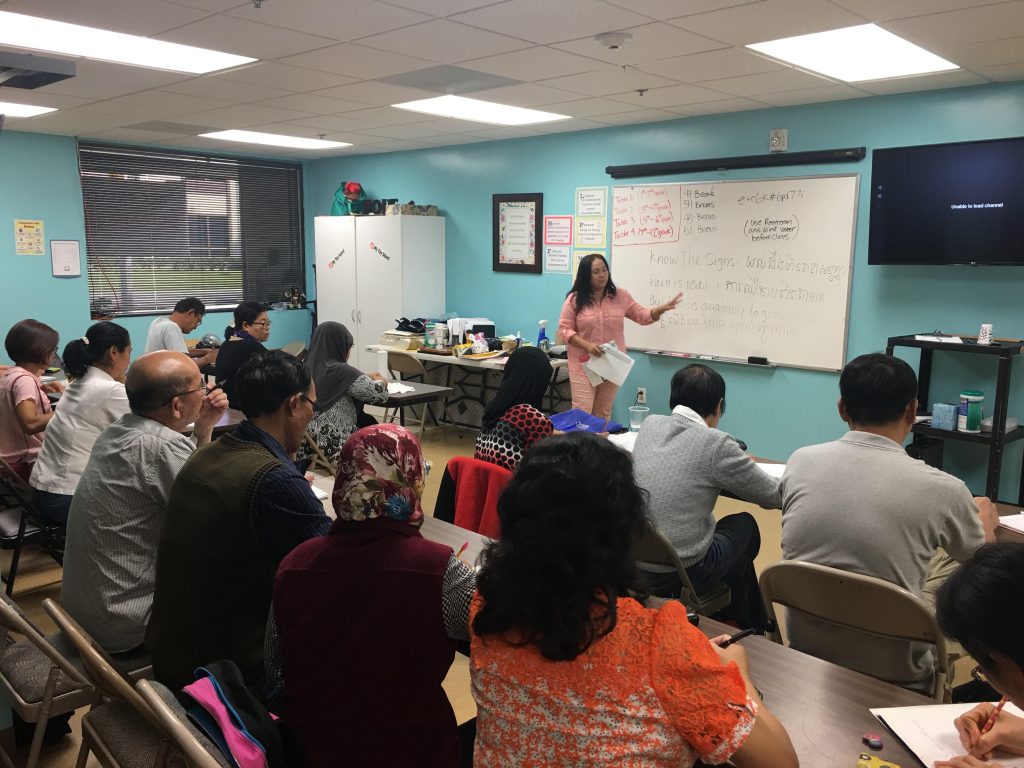

Local community-based organizations like The Cambodian Family Community Center, of Santa Ana, have been a lifeline for community members like Thary and have stepped in to provide vital services where in-language gaps continue to impact those most vulnerable.

Thary Sok receives support in navigating resources from Cambodian Family.

“I met with a doctor in the area, and at that clinic site, they knew about The Cambodian Family community center and how they offer Khmer language interpretation and translation and support in navigating resources,” Thary said, through an interpreter. “So I learned about Cambodian Family through there and sought them out in order to get help.”

Bou, a 71-year-old resident of Santa Ana, moved to the area about a decade ago. It has always been difficult to get the care he needs, but COVID-19 has made the situation even more dire for LEP elders.

“The reason why we are seeking services from The Cambodian Family is because during the COVID-19 pandemic it was very difficult to find resources, one, due to language barriers; and two, because elderly folks do not use a lot of technology or digital devices, making it difficult to schedule appointments online,” Bou said, through an interpreter. “These challenges related to technology are particularly difficult, especially because most things are largely online nowadays. It was easier and more accessible to connect with The Cambodian Family community center because the staff has both the capacity and knowledge to speak to us in our language and share existing resources and services in the community that we need to be connected to.”

“I have experienced various services before, like counseling. However, what was difficult about these kinds of services is that the specialist did not practice and understand my culture, which was made more difficult by the three-way call between the specialist, the interpreter, and myself.”

Another major barrier to mental health care access is stigma within the Southeast Asian American community. Bou, who lives in a multigenerational household with his wife, daughter, son-in-law, and two grandchildren, shares vulnerably that he’s “had issues in accepting and understanding [my daughter’s] health issues, and so that’s made it harder for my daughter to get help, to listen to the doctor, and follow prescriptions—and to reach out to me, her father.”

Kim Song Chhim’s son is often her interpretor at doctor’s appointments.

For many who are able to access mental health care, the treatment may not address cultural experiences or practices. “I have experienced various services before, like counseling. However, what was difficult about these kinds of services is that the specialist did not practice and understand my culture, which was made more difficult by the three-way call between the specialist, the interpreter, and myself,” said Kim Song Chhim, a Santa Ana resident who arrived in theUnited States in 1982.

Kim Song is mother to a daughter and a son, the latter who supports primarily with navigating the healthcare system. Yet, although her son is able to serve as her interpreter, difficulties still linger in translation and communication. This reality can have serious health repercussions, as Kim Song can attest.

“My son once translated a wrong form, so I accidentally took the wrong medication for several days,” she said. “I learned from that experience to seek out help from The Cambodian Family as a case manager to help me translate.”

“For my family, my child is able to help navigate me through resources because he speaks English well, but he is unable to translate well into Khmer, making health appointments difficult. That’s why I need The Cambodian FamilyCommunity Center help to find and request interpretation services from CalOptima and healthcare agencies to provide me with correct translations,” she continued.

The deadly COVID-19 virus has made The Cambodian Family Community Center’s work especially critical for community members like Thary, Bou, and Kim Song.

As Bou summarizes, “Even though I came here about 10 years ago, there are constantly lots of resources, rules, and laws that I have yet to learn about. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, I felt very disconnected from my doctor and health professionals because I was unable to schedule physical check-ups and make appointments in-person. With The Cambodian Family, I have been able to get help with getting referrals to specialists and getting step-by-steps instructions and plans on mental health treatments. I feel like The Cambodian Family Community Center’s staff are my counselors. They support not only my mental health, but also my physical health, because they were able to give me advice and resources to help me resolve my health issues.”

For more information on the mental health needs of Southeast Asian Americans in California, read our report The Right to Heal and factsheets.