September 27, 2021 IN: Community Stories, Our Voices

Ke’s Story: Accepting and healing from harm, but fearing deportation

Listen to Ke’s story here.

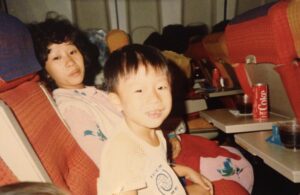

Nghiep “Ke” Lam doesn’t remember his early life in Hai Phong, Vietnam. He would learn later that he and his parents fled Vietnam in late 1977 by boat, after the Viet Cong took over, in fear of persecution for being ethnically Chinese.

He and countless others were stranded in the South China Sea for six months without any fresh water or food. Eventually, they were rescued by a boat of fishermen, who towed them to Hong Kong Refugee Camp — but not before having to give the fishermen everything they owned as payment. They were housed at the camp for two years before obtaining visas to the United States. In 1980, Ke, his brother, and his parents landed in San Francisco.

He and countless others were stranded in the South China Sea for six months without any fresh water or food. Eventually, they were rescued by a boat of fishermen, who towed them to Hong Kong Refugee Camp — but not before having to give the fishermen everything they owned as payment. They were housed at the camp for two years before obtaining visas to the United States. In 1980, Ke, his brother, and his parents landed in San Francisco.

They experienced discrimination early on. One of Ke’s earliest memories is attending a Catholic school, where a nun slapped his hand for not giving a toy to another young classmate who wanted to play with it. His parents removed him from the school and enrolled him in public school. “I always felt different from the other kids, even though there were other Asian kids there. They mocked me, they made fun of me, told me to go back to my country. … I didn’t understand what they were saying to me because I didn’t speak English. But I could tell by their facial expressions that it was not nice.”

When he cried to his mother about being teased, she gave him the advice that she often told him throughout his childhood and adolescence: “Suck it up. Deal with it.” Now that he’s older, Ke realizes that his mother was just trying to survive after becoming a single parent, working two jobs around the clock to make ends meet for him and his brother.

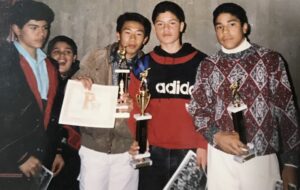

Discrimination followed him to the various places to which their family moved. When living in the projects, at the age of 7, neighborhood kids would throw rotten eggs at him as he walked to school. His teacher would tell him that he was a disruption to the classroom because he didn’t speak English, and Ke would be forced to sit outside in the hallway to wait for the ESL teacher to arrive. Eventually, he began cutting class. He was drawn to the camaraderie of the gang lifestyle.

One day, an immigration officer came to the prison and told him that he lost his status. “I didn’t understand what that meant,” he said. “Growing up, I didn’t have a recollection of coming to America. I didn’t know I was a refugee. My family never talked about that.”

One night, shortly after his 17th birthday, Ke made a decision that changed his entire life. Trying to prove his worth to the other members of his gang, he fatally stabbed a member of a rival gang. “Part of me was in denial about what I was doing,” he says. “I didn’t accept that I could do such harm to another person.”

His arrest traumatized his family. “My mother was shocked that her son did something so wrong that the police would take him away,” he said. “My siblings cried and asked my mom, ‘Why?”

Ke’s conviction brought him to several prisons. One day, an immigration officer came to the prison and told him that he lost his status. “I didn’t understand what that meant,” he said. “Growing up, I didn’t have a recollection of coming to America. I didn’t know I was a refugee. My family never talked about that.” Ke insisted he was born in the United States. Later, his mom would tell him that he actually arrived to the country at the age of 4.

In prison, Ke turned his life around. He stopped cursing, stopped drinking, and stopped smoking. “Anything I did as my former self that led me to harming others and taking a life, I denounced,” he explained. He went to church, played sports, earned his GED, and became a mentor in a youth mentorship program. It was a transformational experience for Ke.

In prison, Ke turned his life around. He stopped cursing, stopped drinking, and stopped smoking. “Anything I did as my former self that led me to harming others and taking a life, I denounced,” he explained. He went to church, played sports, earned his GED, and became a mentor in a youth mentorship program. It was a transformational experience for Ke.

“For me, I thought it was me being a mentor to these young folks and teaching them something, but in reality they were teaching me a lot about who I was, about my young past that I had forgotten about—connecting with the hurt, the shame, the struggles, dealing with feeling abandoned as well as dealing with trauma, neglect, and abuse not just from family but also people around there in their community. That helped me a lot and opened my eyes to dealing with my own stories that I needed to make amends for the harm that I caused to my victim’s family as well as my own family and my community.”

After serving 22 years in prison, Ke was found suitable for parole. Rather than enjoying his freedom on the day of his release, Ke was immediately picked up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and was transferred to a detention facility. Ke was detained for five more months, during which time he was processed for deportation. “It felt like I was being double punished. A terrible crime that I committed when I was a youth would eventually lead to my deportation to a country that I had no ties to. I felt like I was unworthy, not valued, that all that I’d done to change my life, to build community while I was inside, doesn’t matter.”

After serving 22 years in prison, Ke was found suitable for parole. Rather than enjoying his freedom on the day of his release, Ke was immediately picked up by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and was transferred to a detention facility. Ke was detained for five more months, during which time he was processed for deportation. “It felt like I was being double punished. A terrible crime that I committed when I was a youth would eventually lead to my deportation to a country that I had no ties to. I felt like I was unworthy, not valued, that all that I’d done to change my life, to build community while I was inside, doesn’t matter.”

Because of an agreement with the United States and Vietnam, Ke was allowed to stay in the United States because Vietnam was not accepting people with removal orders who arrived in the United States prior to 1995.

These last five years, Ke has lived in limbo. While he waits, Ke has a commitment to making a difference in the world, and serves as a reentry coordinator for Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC). “For me, that is my healing. That is something I’m passionate about now. I started volunteering for APSC, and I’ve been here ever since. This is an organization I’ll be with until I retire.”

Take action and urge your members of Congress to support the New Way Forward Act, which would provide further relief for Danny. A digital toolkit is available here. It includes SEAA stories, graphics, quotes, and other advocacy tools that you can use to encourage your reps to co-sponsor the bill.

Take action and urge your members of Congress to support the New Way Forward Act, which would provide further relief for Danny. A digital toolkit is available here. It includes SEAA stories, graphics, quotes, and other advocacy tools that you can use to encourage your reps to co-sponsor the bill.