May 25, 2021 IN: Community Stories, Our Voices

Brothers and Sisters

by Vichet Chhuon

Brothers and sisters have unique bonds. We play together and against each other. We compete for attention from our parents. We also take each other for granted. Our siblings shape us in profound ways. Consider how different we would be without them.

For immigrant children, our brothers and sisters take on additional roles, like helping to raise us while our parents work and acting as cultural brokers in a new place.

Growing up, my big sister, Sopheaktra “Pat,” helped to keep me out of trouble… well, she did the best she could. Pat was four years older, which was enough to effectively stand up for me when I was little. She was the smart one. And so it mattered when she lobbied my parents to let me do things other kids were allowed to do. She spoke with my teachers when I acted out in class. Even when she and I fought, and we did, and we do — I know I am the way I am because of how she was. Pat has always demonstrated incredible strength through adversity, even as a baby in the worst conditions imaginable.

We are a refugee family from Cambodia. Growing up, we heard lots of stories of life during “Pol Pot time.” They were shared openly in our family. These types of stories flowed in our house, often with sadness, followed by tears, sometimes with anger, once in a while humor, and almost always with relief. I’ve heard a lot of them, but I hadn’t heard this one until my own daughter was born last year, when my parents came to visit.

The story takes place before I was born.

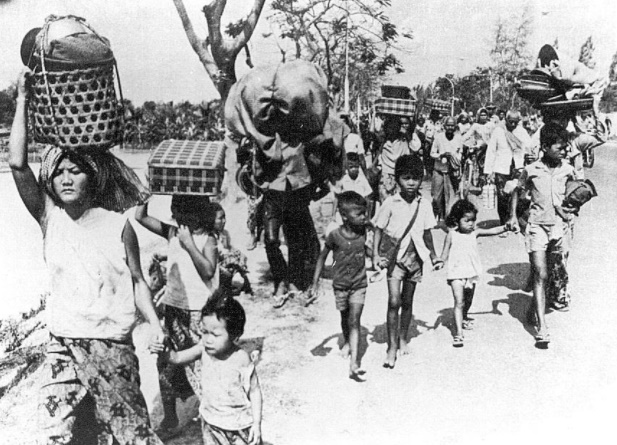

It was early June 1975, six weeks after Khmer Rouge soldiers marched into Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh, and forced the country’s urban dwellers into the countryside as part of an ambitious and brutal agrarian communist revolution.

Phnom Penh, April 17, 1975 (Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives)

To keep safe, families traveled in groups. My parents had two children at the time, my big sisters: Sokchenda “Nda” and Sopheaktra “Pat.” Nda was no more than four and Pat was barely walking. Pat was carried the entire way. Nda struggled to keep up by foot. So they mostly carried her too.

One night, after walking along dirt roads for over a month, Pat had a high fever. She was coughing throughout the day. The cough and high temperature stayed with her most of the night. My family, along with a few other travelers, were on route to a forced labor camp. They were confused and scared.

That night, my parents braced for the worst.

Source: Documentation Center of Cambodia Archives

My dad, sitting in my kitchen, confessed stoically that he thought that Pat would be lost that night. My mother, seated next to him, still and serious, explained that they had already witnessed others die during their travel.

That evening forty years ago, both explained, all they could do was pray.

After dark, a neighbor helped boil some rice porridge “bobor” for Pat to eat. Even today, bobor is something we eat when we’re sick. Bobor nourishes our bodies. But it seems to nourish us in other ways as well. That entire night, my mother held little Pat as she slept. Everyone prayed. Pat survived the night and became increasingly well in the next few days.

I was born two years later in a Khmer Rouge labor camp in Battambang province in northwestern Cambodia. Another two years after that, the Vietnamese army invaded the country. Many Cambodians, including my parents, now with three young children, fled to the Thai border. Many didn’t make it. Others lucky enough to make it found refuge in United Nations sponsored “camps” in Thailand.

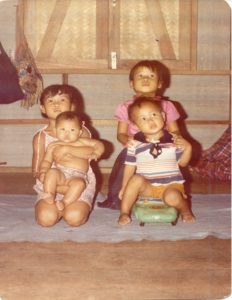

Khao-I-Dang Refugee Camp, 1980

In this photo, Pat is at the top right, with me. The baby is my sister, Siemny, who was born in Khao-I-Dang, and big sister Nda is holding her. We stayed in Khao-I-Dang refugee camp for about a year before being accepted for asylum and admitted as refugees to the U.S. in 1981.

It’s not surprising that Pat would survive that night in 1975, if you know her. After we came to the U.S., she endured a tough home life as an immigrant Cambodian daughter. We were poor. We were Asian Americans but apparently not the “good” Asians people talked about. She also endured a school system that tried to invalidate our cultural identities. Pat helped me with that too. My sister took care of all us. As brothers and sisters do, we took care of each other the best we could.

Vichet Chhuon is an associate professor of culture and teaching at the University of Minnesota. His three siblings are Siemny, Sopheaktra “Pat” and Sokchenda “Nda”.

This article was originally published in 2015 as a part of SEARAC’s 40 And Forward campaign, celebrating 40 years of the Southeast Asian American experience. We are re-sharing this story and others during May and June 2021 in honor of World Refugee Day.