May 31, 2019 IN: Community Stories, Our Voices

Pele’s Story: Bridging My Vietnamese Identity To Our Southeast Asian Advocacy

This is me. Pele Văn Lê.

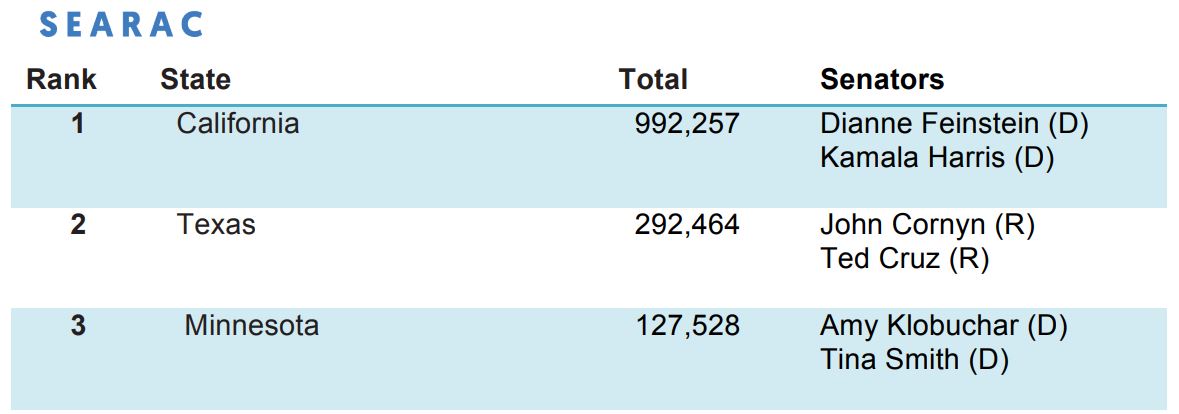

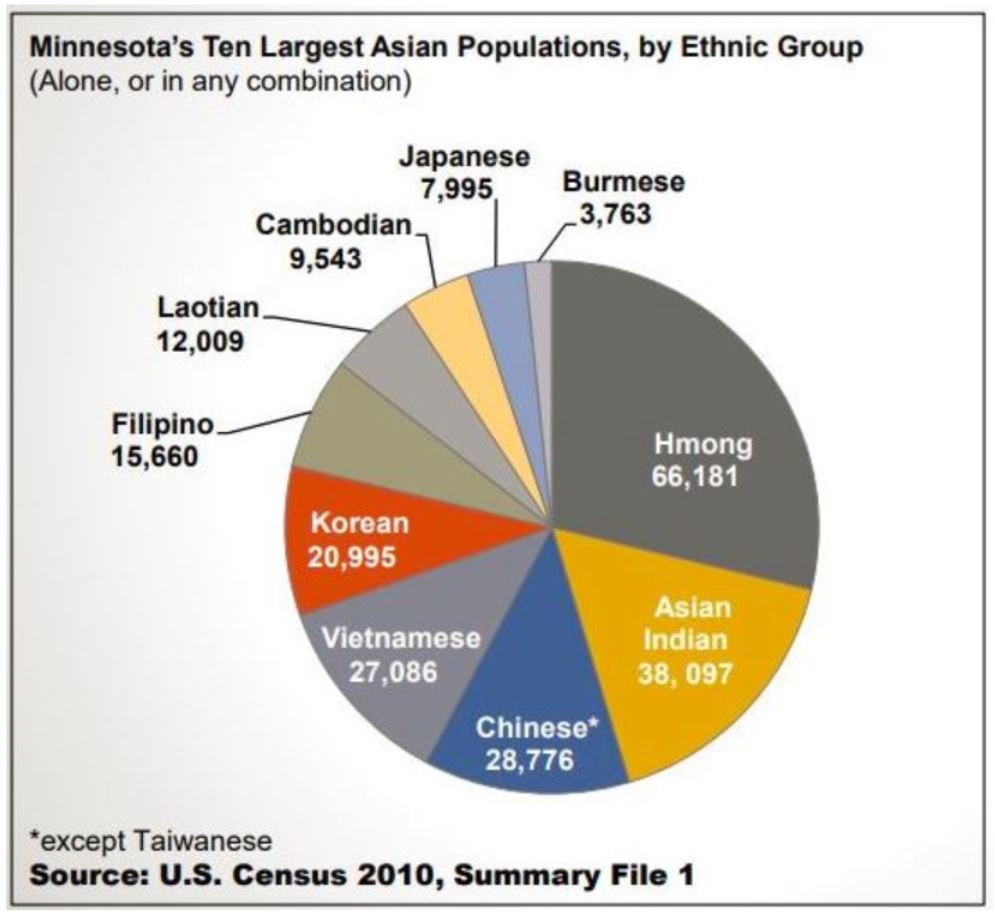

My name is Pele Văn Lê (he/him/his), and I am a second-generation Vietnamese American who was born and raised in Minnesota. My resilient father, a boat refugee, and my unconditionally loving mother, an Amerasian, who are both refugees of the war in Vietnam, named all of my brothers and I after soccer/football players – in my case, the Brazilian football player Pelé. In Minnesota, there is a significant population of people of color and minorities. In fact, Minnesota ranks 3rd for highest Southeast Asian population with over 125,000 people in the United States; almost 3% of the state’s total population.

Source: https://www.searac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Top-SEAA-states-fact-sheet.116th-Congress.jpg

Source: U.S. Census 2010, Summary File 1

Growing up as a second-generation Vietnamese American, my parents worked seven days a week to keep a roof over our heads and our bodies from starvation. As my parents worked for our survival, at school I struggled finding community and guidance. Attending predominantly white institutions, every interaction was a trigger that reminded me I was Asian and a minority – inferior and undesired. Inevitably, I proactively assimilated to whiteness by neglecting my Vietnamese heritage, changing my appearance, and giving in to toxic behaviors. It was only until college that I reflected and realized I grew up feeling ashamed and hurt myself because of our capitalistic-driven society and racism.

My best friends from middle school

Healing–in this case, recognizing and building interdependent relationships–began when I found refuge within the Southeast Asian community. Although I was Vietnamese, I grew up gravitating and more connected to the Hmong community. As I struggled and experienced discrimination, my community was there to on which to lean and be in solidarity. It was only later when I realized our experiences from the war in Vietnam tied together our Vietnamese and Hmong identities. Throughout the rest of my secondary education, the solidarity from the community helped me embrace and become more prideful of my racial and ethnic identity, pushing me through the most unhealthy and difficult moments of my life.

My grandmother and grandfather (Bà Ông Ngoại) at my high school graduation ceremony

As a first-generation college student, I encountered a lot of barriers to higher education, but despite the challenges, I had the opportunity to stay in-state and attend the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. Because staying local was affordable and gave me access to my parents, it was the best choice to minimize any burden on my family. Upon entering college, I was confused on what to pursue, but I knew clearly I was driven by my faith in community and my struggles in health. This led me to pursue pre-medicine studies and engage in student activism.

Emceeing at the Vietnamese Student Association of Minnesota’s 2017 Annual Lunar New Year Show

Along with my studies, being a student activist and community organizer were significant identities that cultivated my passion in health and social justice. Because of the lack of community and resources growing up, I took on these roles to create resources that did not exist. We proactively facilitated inclusive spaces and created programs to build mentorship, develop leadership skills, celebrate our identities, and uplift our stories. These experiences also taught me how privileged it is to do this work; you had to have time, financial stability, and access.

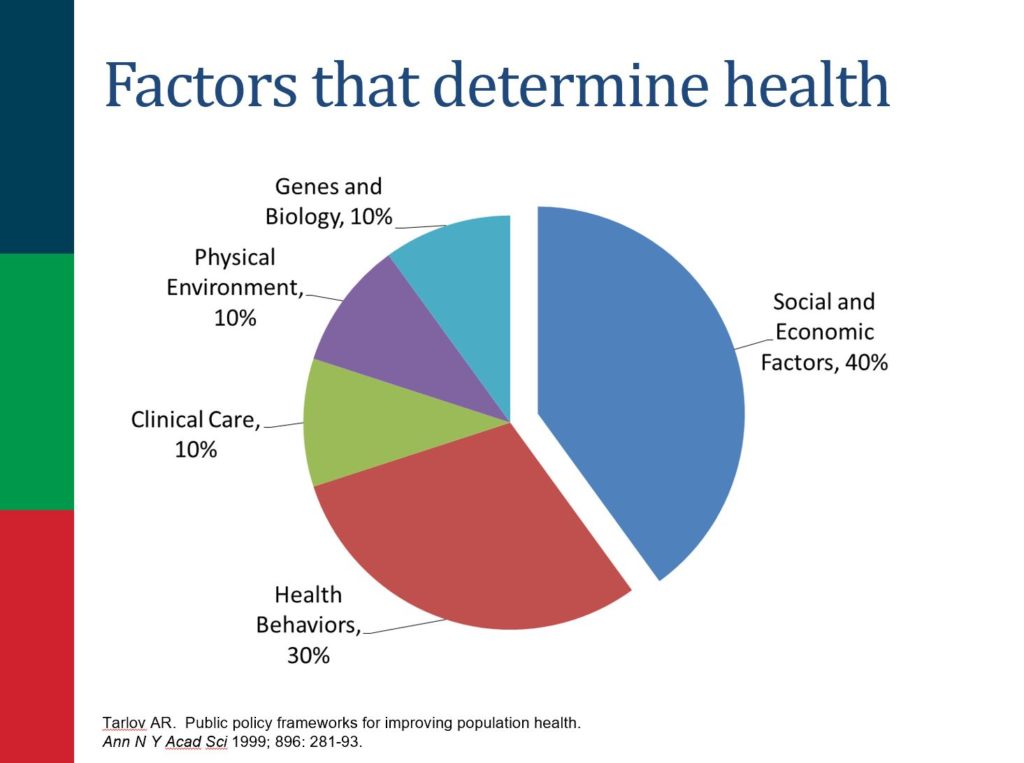

These programs were important, but they were all short-term solutions to greater long-term challenges – structural violence and racism. Because behaviors and social and economic factors contributed to most of our health, I began to realize our community would continue to lack resources because of the inequitable distribution of resources which government and policies are responsible for. To equip myself to combat the injustice I felt, I changed my major to healthcare management with a minor in public health, psychology, leadership, and Asian languages and literature.

Every single aspect of our lives is touched by the government, yet communities are not civically engaged or voting. I don’t blame them, though. Like myself, I was apathetic and didn’t understand how systems structurally harmed or benefited me. But, it was clear to me – to create a better society, we must actively decide to civically engage because civic engagement is a privilege. For some, it is not a decision but the only means for survival. My parents—they did not choose to have a war in home country, to have their parents fight and die in the war, or to become an orphan, but the war still took place and caused immeasurable amounts of suffering.

I don’t want my community to just survive and struggle day-to-day like my family did. I want my community and family to thrive and live in peace. So, every day I do my best to be civically engaged with my community.

College graduation day with my family

Graduation arrives. I am a first-generation college graduate, and life is more turbulent than ever. I have no idea what to do next. It was a perplexing moment when I stood there on my graduation, accomplishing what my parents never had the opportunity to access. Yet after, I felt more stressed and confused than ever.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/searac

Then, the opportunity emerged to intern at SEARAC. With hesitation, knowing I would have to leave my family and not have reliable housing or financial stability, I accepted to pursue a career/life where I can continue advocating for myself and my community.

SEARAC speaks out publicly against the harmful detention and deportation policies that are ripping Southeast Asian American families apart. (2/27/2019).

Source: https://www.facebook.com/searac/videos/2207865132812199/

Through my time at SEARAC, I was exhausted, emotionally and spiritually, because I felt hopeless becoming aware of so many injustices that are harming our community and not being able to do anything to address them. It’s really true: You don’t know what you don’t know (obviously). Understanding the connection between USnited States federal policy and our individual lives is hard and oppressive. What activated me the most was learning how groups are proactively advocating for policies that discriminate against our community, so they can continue to dominate our society.

What SEARAC strives to bridge is exactly that connection, bringing awareness of issues deriving from federal and state policy, sharing how it positively or negatively impacts our families, such as, deportation, health access, and data collection, and mobilizing us to take action to address injustices.

There are a lot of challenges we face as a community, but I believe tackling any of them begins with embracing our own identity. Being Southeast Asian not only means we are people who have roots from Southeast Asia, but more significantly, we are all connected by our collective struggle and the war in Vietnam. Loss of home, starvation, uncontrollable trauma, death of family, and pain are only few of the adversities that makes our community so resilient and connected. This makes it even more important for community to continue building and sharing our stories.

My last day at SEARAC (missing: Lee Lo and Nkauj lab Yang)

Working with SEARAC and the staff of 10 for the past couple months has been a transformative experience and I cannot thank them and everyone who has helped me evolved. For those who lacked mentors growing up like I did, I can confidently tell you we have a fruitful community of resilient leaders (you are also your own mentor).

As a proud second-generation Vietnamese American, my story is one of many collections of narratives that is a part of SEARAC and the Southeast Asian movement. Through claiming my own narrative, embracing my unique upbringing with all of its privileges and disadvantages, and being shamelessly unapologetic, I have found my calling to community building and living with purpose. To me, that is advocacy — waking up and making the purposeful decision to accept my complexity and taking action when I see injustice.

Pele Văn Lê interned with SEARAC in the spring of 2019. He currently works as Events and Operations Programs Associate at the Institute for Educational Leadership.