Navigating Mental Health as a Khmer Social Worker

by Nary Rath

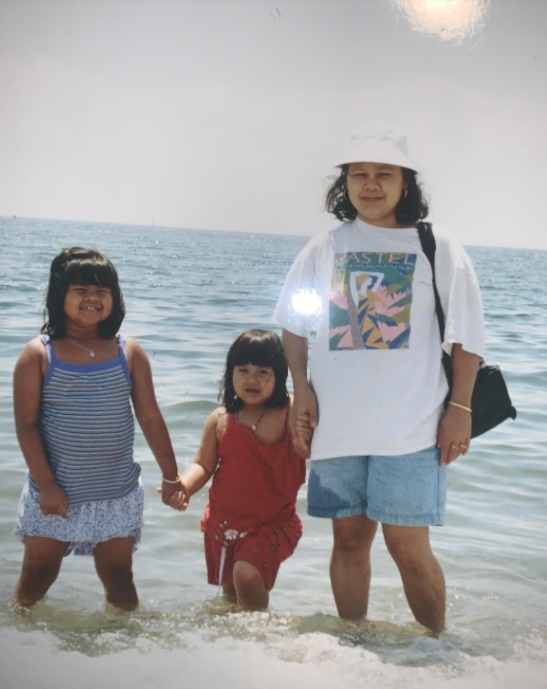

My mom arrived to the United States in 1983 fleeing from war and genocide to seek refuge. She was 21 years old when she started a new life in Ohio and then set roots in Connecticut, where she raised my older sister and me. Rebuilding her life in this country has led to opportunities never imaginable for my family in Cambodia, but the exposure to pre- and post-migration trauma continues to be felt by entire communities of Southeast Asian Americans (SEAAs).

Surviving genocide, long-term exposure to violence, displacement, and anti-immigrant racism in the United States are all factors that contribute to the high prevalence of mental health issues for SEAA refugees. Even decades after resettlement, SEAA communities continue to face high rates of adverse mental health conditions, such as major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders. Continued anti-immigrant racism and oppression perpetuated by the US government through discriminatory policies, from aggregated racial data to systematic deportation, exacerbates the barriers that prevent SEAA communities from thriving. Poor access to culturally and linguistically appropriate health care in this country furthers the severity of these conditions, making the cycles of trauma difficult to break and healing out of reach for many.

I’ve learned that intergenerational trauma has personally impacted me, and through diligent mental healthcare, I’ve worked to heal from painful past experiences. Through a journey of discovering love, empathy, and a compassion for myself and my family history, I’ve learned to dismantle internalized oppression and deconstruct my trauma.

During my first experience working with refugees, I co-facilitated a psycho-social wellness group. We used beauty application as an intervention that aimed to restore trust and build a sense of community for female survivors of torture. Through this experience working with the refugee community, I realized how much it hit home for me to work with clients that had such little trust in others that it was difficult to even have someone apply nail polish on them. As a social worker, I’ve learned that without treating the severe trauma that’s endured by oppressed groups such as SEAA refugees, aspects of poor mental and emotional conditions can be passed onto future generations — this is called intergenerational trauma. The children and grandchildren of refugees can develop attachment issues and isolation as a result of being raised by parents who display psychological distress from experiencing massive group trauma.

Nary (middle), mom and sister

From a young age I knew that my family was different: we were poor, my dad had uncontrollable anger issues, and my sister exhibited self-injurious behaviors. But because mental health care is highly stigmatized within the SEAA community, it was never talked about and even shamed if brought up. I distinctly recall a time my mom brought my sister to a Buddhist healer because she thought my sister was possessed by demons, when in reality she was struggling with poor mental health conditions. My fight-or-flight response was often activated in my childhood as a reaction to stress. Your sympathetic nervous system is responsible for triggering fight-or-flight responses, where the body may experience a faster heart beat, shortness of breath, and a release of adrenaline into the bloodstream. This is the body’s way of responding to perceived dangers as a mechanism for survival. But chronic activation of this survival mechanism can have lasting impairments to your health. I’ve learned that intergenerational trauma has personally impacted me, and through diligent mental healthcare, I’ve worked to heal from painful past experiences. Through a journey of discovering love, empathy, and a compassion for myself and my family history, I’ve learned to dismantle internalized oppression and deconstruct my trauma.

But my journey to healing wasn’t easy — it was often met with judgement from members of my community, friends, and family. In order for our communities to flourish, we must advocate for policies that promote culturally appropriate and trauma-informed social services, support research of cross disciplinary mental health interventions, and address stigma by normalizing conversations surrounding mental health. Without bringing SEAA voices to the table where policy decisions are made, we cannot advocate for the major mental health needs of our community. We can honor our ancestors and family histories of resilience and strength by showing up for ourselves and the next generation through breaking generational cycles of trauma.

**Pictured at top, Nary (front) and sister

Nary Rath is SEARAC’s Immigration Policy Advocate. To contact Nary, email nary@searac.org.

Pele’s Story: Bridging My Vietnamese Identity To Our Southeast Asian Advocacy

This is me. Pele Văn Lê.

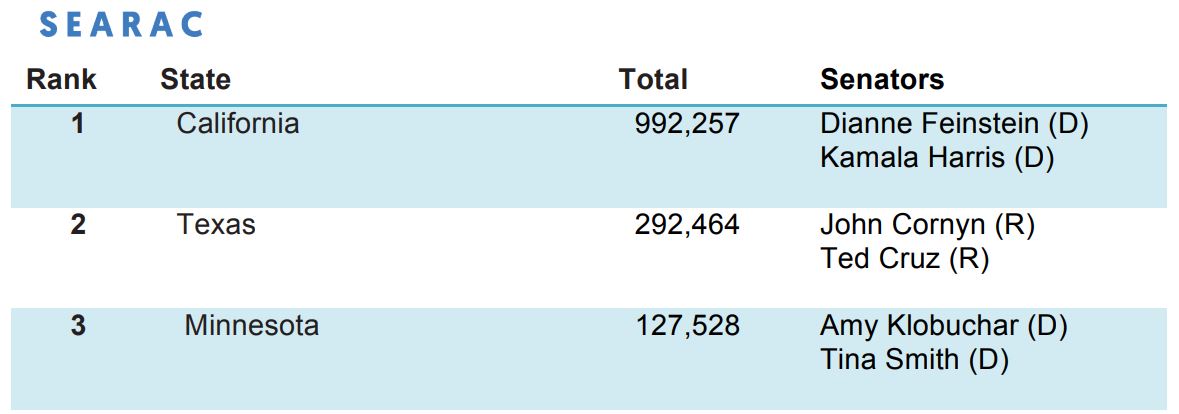

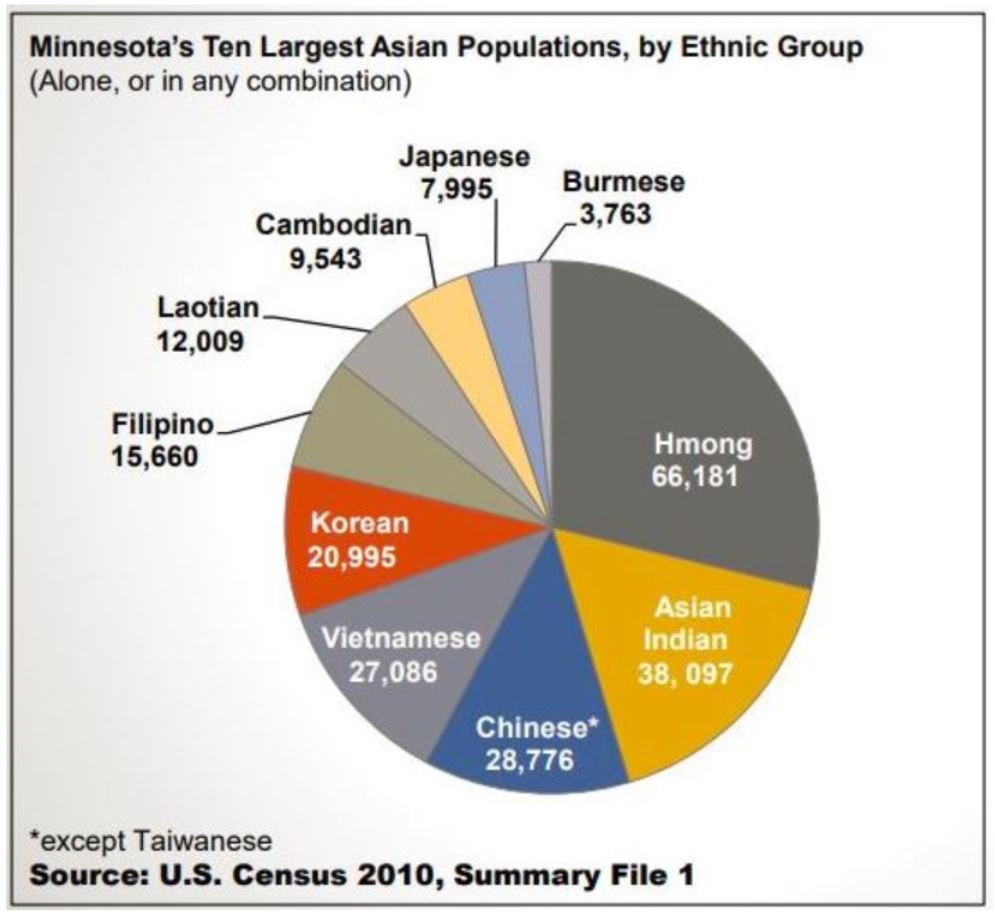

My name is Pele Văn Lê (he/him/his), and I am a second-generation Vietnamese American who was born and raised in Minnesota. My resilient father, a boat refugee, and my unconditionally loving mother, an Amerasian, who are both refugees of the war in Vietnam, named all of my brothers and I after soccer/football players – in my case, the Brazilian football player Pelé. In Minnesota, there is a significant population of people of color and minorities. In fact, Minnesota ranks 3rd for highest Southeast Asian population with over 125,000 people in the United States; almost 3% of the state’s total population.

Source: https://www.searac.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Top-SEAA-states-fact-sheet.116th-Congress.jpg

Source: U.S. Census 2010, Summary File 1

Growing up as a second-generation Vietnamese American, my parents worked seven days a week to keep a roof over our heads and our bodies from starvation. As my parents worked for our survival, at school I struggled finding community and guidance. Attending predominantly white institutions, every interaction was a trigger that reminded me I was Asian and a minority – inferior and undesired. Inevitably, I proactively assimilated to whiteness by neglecting my Vietnamese heritage, changing my appearance, and giving in to toxic behaviors. It was only until college that I reflected and realized I grew up feeling ashamed and hurt myself because of our capitalistic-driven society and racism.

My best friends from middle school

Healing–in this case, recognizing and building interdependent relationships–began when I found refuge within the Southeast Asian community. Although I was Vietnamese, I grew up gravitating and more connected to the Hmong community. As I struggled and experienced discrimination, my community was there to on which to lean and be in solidarity. It was only later when I realized our experiences from the war in Vietnam tied together our Vietnamese and Hmong identities. Throughout the rest of my secondary education, the solidarity from the community helped me embrace and become more prideful of my racial and ethnic identity, pushing me through the most unhealthy and difficult moments of my life.

My grandmother and grandfather (Bà Ông Ngoại) at my high school graduation ceremony

As a first-generation college student, I encountered a lot of barriers to higher education, but despite the challenges, I had the opportunity to stay in-state and attend the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. Because staying local was affordable and gave me access to my parents, it was the best choice to minimize any burden on my family. Upon entering college, I was confused on what to pursue, but I knew clearly I was driven by my faith in community and my struggles in health. This led me to pursue pre-medicine studies and engage in student activism.

Emceeing at the Vietnamese Student Association of Minnesota’s 2017 Annual Lunar New Year Show

Along with my studies, being a student activist and community organizer were significant identities that cultivated my passion in health and social justice. Because of the lack of community and resources growing up, I took on these roles to create resources that did not exist. We proactively facilitated inclusive spaces and created programs to build mentorship, develop leadership skills, celebrate our identities, and uplift our stories. These experiences also taught me how privileged it is to do this work; you had to have time, financial stability, and access.

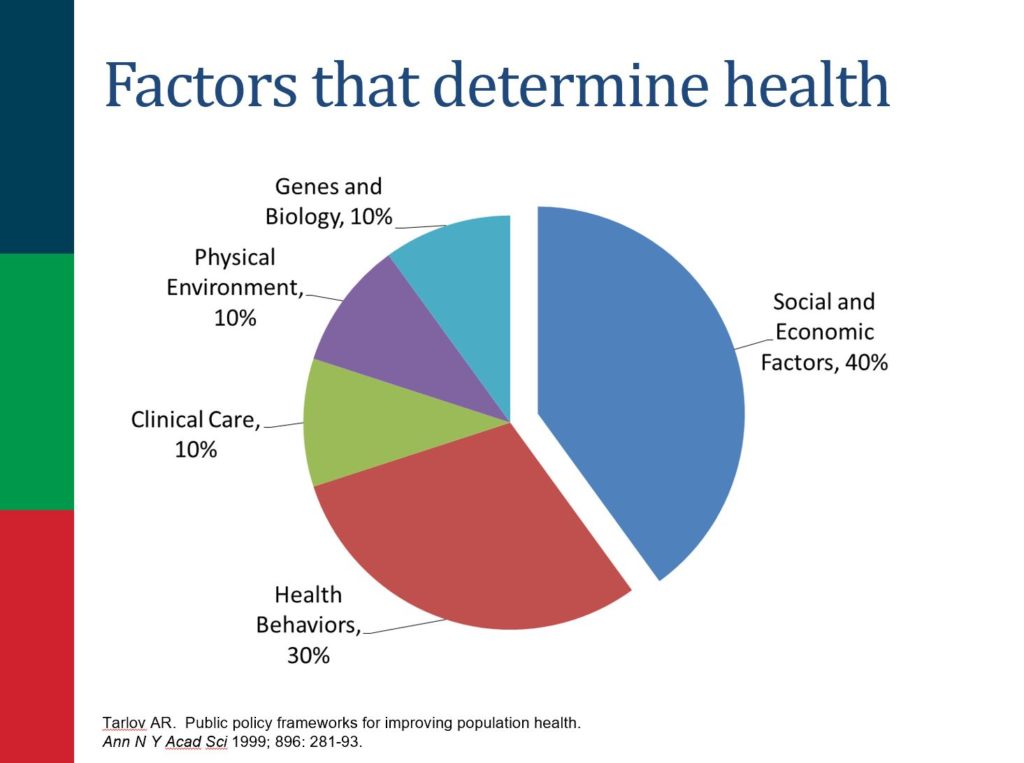

These programs were important, but they were all short-term solutions to greater long-term challenges – structural violence and racism. Because behaviors and social and economic factors contributed to most of our health, I began to realize our community would continue to lack resources because of the inequitable distribution of resources which government and policies are responsible for. To equip myself to combat the injustice I felt, I changed my major to healthcare management with a minor in public health, psychology, leadership, and Asian languages and literature.

Every single aspect of our lives is touched by the government, yet communities are not civically engaged or voting. I don’t blame them, though. Like myself, I was apathetic and didn’t understand how systems structurally harmed or benefited me. But, it was clear to me – to create a better society, we must actively decide to civically engage because civic engagement is a privilege. For some, it is not a decision but the only means for survival. My parents—they did not choose to have a war in home country, to have their parents fight and die in the war, or to become an orphan, but the war still took place and caused immeasurable amounts of suffering.

I don’t want my community to just survive and struggle day-to-day like my family did. I want my community and family to thrive and live in peace. So, every day I do my best to be civically engaged with my community.

College graduation day with my family

Graduation arrives. I am a first-generation college graduate, and life is more turbulent than ever. I have no idea what to do next. It was a perplexing moment when I stood there on my graduation, accomplishing what my parents never had the opportunity to access. Yet after, I felt more stressed and confused than ever.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/searac

Then, the opportunity emerged to intern at SEARAC. With hesitation, knowing I would have to leave my family and not have reliable housing or financial stability, I accepted to pursue a career/life where I can continue advocating for myself and my community.

SEARAC speaks out publicly against the harmful detention and deportation policies that are ripping Southeast Asian American families apart. (2/27/2019).

Source: https://www.facebook.com/searac/videos/2207865132812199/

Through my time at SEARAC, I was exhausted, emotionally and spiritually, because I felt hopeless becoming aware of so many injustices that are harming our community and not being able to do anything to address them. It’s really true: You don’t know what you don’t know (obviously). Understanding the connection between USnited States federal policy and our individual lives is hard and oppressive. What activated me the most was learning how groups are proactively advocating for policies that discriminate against our community, so they can continue to dominate our society.

What SEARAC strives to bridge is exactly that connection, bringing awareness of issues deriving from federal and state policy, sharing how it positively or negatively impacts our families, such as, deportation, health access, and data collection, and mobilizing us to take action to address injustices.

There are a lot of challenges we face as a community, but I believe tackling any of them begins with embracing our own identity. Being Southeast Asian not only means we are people who have roots from Southeast Asia, but more significantly, we are all connected by our collective struggle and the war in Vietnam. Loss of home, starvation, uncontrollable trauma, death of family, and pain are only few of the adversities that makes our community so resilient and connected. This makes it even more important for community to continue building and sharing our stories.

My last day at SEARAC (missing: Lee Lo and Nkauj lab Yang)

Working with SEARAC and the staff of 10 for the past couple months has been a transformative experience and I cannot thank them and everyone who has helped me evolved. For those who lacked mentors growing up like I did, I can confidently tell you we have a fruitful community of resilient leaders (you are also your own mentor).

As a proud second-generation Vietnamese American, my story is one of many collections of narratives that is a part of SEARAC and the Southeast Asian movement. Through claiming my own narrative, embracing my unique upbringing with all of its privileges and disadvantages, and being shamelessly unapologetic, I have found my calling to community building and living with purpose. To me, that is advocacy — waking up and making the purposeful decision to accept my complexity and taking action when I see injustice.

Pele Văn Lê interned with SEARAC in the spring of 2019. He currently works as Events and Operations Programs Associate at the Institute for Educational Leadership.

Quyên Đinh

Quyên is the Executive Director of the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC). Originally formed in 1979, SEARAC was founded by a group of American humanitarians as a direct response to the refugee crises arising throughout Southeast Asia as a result of U.S. military actions. Today, SEARAC is a civil rights organization that represents the largest refugee community ever resettled in America. It works to empower diverse communities from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam to create a socially just and equitable society through policy advocacy, advocacy capacity building, community engagement, and mobilization.

As Executive Director, Quyên has advocated for Southeast Asian Americans on key civil rights issues including education, immigration, criminal justice, health, and aging. Quyên has spoken widely about Southeast Asian American communities and has appeared in American RadioWorks, NBC, Public Radio International, and Voice of America. Under Quyên’s leadership, SEARAC has authored national legislation and passed California legislation calling for transparent, disaggregated data for the Asian American community. Quyên has also extended SEARAC’s coalition presence and leadership in other civil rights and social justice movements through her leadership roles with the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA), Detention Watch Network (DWN), the Diverse Elders Coalition (DEC), RISE for Boys and Men of Color, and Allies Reaching for Community Health Equity (ARCHE) Action Collaborative. Prior to SEARAC, she built lasting infrastructure for the International Children Assistance Network (ICAN) in San Jose, CA, serving Vietnamese immigrant parents, grandparents, and youth.

Born to Vietnamese refugees, Quyên identifies as a second-generation Vietnamese American. She holds a Master of Public Policy degree from the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from the University of California, Berkeley. Quyên was born in New Orleans, LA, and grew up in Orange County, CA, and San Jose. She currently resides with her husband in Washington, DC.

pronouns: she/her/hers

Open Letter to The Washington Post

Southeast Asian American students cannot erase their refugee legacies

In “The Forgotten Minorities of Higher Education” published March 18, conservative strategist Ed Blum, who is leading a charge to end affirmative action at Harvard, wonders “Do we want to elevate our race and our ethnicity to the most existential part of who we are?” In other words, if students cannot separate their race from their identities, he argues, the country is “at a very bad gateway.”

Only in a world where historical and structural inequalities no longer dictate who gets resources should race and ethnicity not be considered. But this utopia does not exist. In reality, only 14% of Laotian, 17% of Hmong and Cambodian, and 27% of Vietnamese Americans have a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 54% of Asian Americans overall.

Blum’s rhetorical question dismisses the barriers Southeast Asian American communities have had to overcome as part of their experiences as the children of refugees. Contrary to the myth of the model Asian minority, Southeast Asian Americans face numerous obstacles to college access, such as high rates of poverty, limited English proficiency, and underresourced schools. At the same time, our students’ experiences–and their resilience and perseverance–that are associated with their racial, ethnic, and historical backgrounds are formative and central to their sense of identity. Our students’ self-determination in the face of structural challenges cannot and should not be erased.

Katrina Dizon Mariategue

As SEARAC’s first ever Chief Operating Officer, Katrina provides strategic management and oversight of the organization’s infrastructure, which includes finance and grants administration, human resources, and operations to ensure that SEARAC has the capacity to achieve its mission. Katrina started out as SEARAC’s immigration policy manager, where she advocated to keep Southeast Asian American families safe from deportation. She has appeared in a number of publications including, NBC News, AJ+, Huffington Post, Public Radio International, NPR, and the Nation, expanding SEARAC’s immigration policy and mass incarceration work to reach broader audiences. Following this role, Katrina served in various leadership positions in SEARAC, including Director of National Policy, Deputy Director of Policy and Field, and Acting Executive Director.

Before coming to SEARAC, Katrina worked in the labor movement for six years at the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO). In 2011, she was elected to serve as DC chapter president of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA), the only national Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) union membership organization. In this capacity, she led the chapter’s local advocacy campaigns and organizing work around immigrant workers’ rights, coordinated civic engagement programs for the 2012 elections, and strengthened local networks through extensive coalition building efforts. She also served on APALA’s National Executive Board and co-chaired the organization’s Young Leaders Council.

Katrina holds a Master of Public Policy degree from the University of Maryland, College Park, where she also served as graduate coordinator at the Office of Multicultural Involvement and Community Advocacy to advise, mentor, and educate AAPI students on campus. She received her bachelor’s degree from Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. In her free time, Katrina enjoys spending time with her daughter and husband, binge-watching true crime series on Netflix, reading dystopian fiction, swimming, and watching Broadway musicals.

pronouns: she/her/hers

Language and the Southeast Asian diaspora

I want to talk about the power of language; not necessarily the power of individual words and phrases, but the power of language as a whole. The language/languages an individual speaks plays a role in both constructing and expressing his or her identity. Speaking a language is a direct connection to a community of people, a place, and a culture. In a majority English-speaking country like the United States, speaking a different language is an expression of identity.

Earlier this year, a white lawyer overheard restaurant workers speaking Spanish and threatened to call ICE. He told the manager, “They should be speaking English. … This is America.” Earlier this month, a woman in Portland, OR, directed a racist rant at a Filipino American woman, all in a mock Asian accent. These individual incidents of bigotry and prejudice bring up a new question: is speaking a language other than English becoming dangerous in the United States?

While I may not have a personal response to the dangers of speaking another language, I do know it is an undeniably scary trend. It is becoming increasingly important to create and find spaces in the United States, specifically, for immigrant families to speak freely in their first language. Those spaces were important to me growing up because they served as a connection to my mother’s language and culture, and especially to my grandparents who struggled to learn English. Speaking a language other than English in the United States can be marginalizing — from available job opportunities to being a target for xenophobic comments. At the same time, language acts as a joining force to allow Southeast Asian Americans to find others who share similar experiences and connect with those who may feel similarly displaced in the English-dominated United States.

Languages as a connection to a people and place have been an important part of my life, showing me that spaces are defined by the languages spoken in it. I’ve seen how a grocery store becomes a community gathering place when all the price labels and employees speak Vietnamese. When I was growing up, the Vietnamese population all seemed to live in the same area of the city — brought together by a shared desire of solidarity in language and culture. I would go shopping with my grandparents every Saturday morning at a Vietnamese market and make the occasional trip to Our Lady of La Vang Church. I grew up speaking English in my home and at school, but would be brought to spaces where Vietnamese was the only language spoken. This duplicity has defined my experience as a second generation immigrant.

It is important to understand the connection between language and identity in the United States. While it serves as a force to bring together the Southeast Asian diaspora in the United States, it can also be something immigrant families struggle to connect with their identities as both immigrants and Americans.

Vina Alexander is SEARAC’s fall field and outreach intern. She is in her third year at Lewis and Clark College in Portland, where she is majoring in political science.

Are you our next Immigration Policy Advocate?

Priority deadline extended to August 15

Finding Community, Finding Myself

I have always known my culture to be the smell of thịt kho and nước mắm emanating from the kitchen, red envelopes during Tết, and navigating through the countless honorifics that I have to call my family members. However, growing up as a Vietnamese American in a predominantly white, conservative area of the Midwest taught me that my history and culture were nothing more than a moment of war and containment in American history. I had no idea that a Southeast Asian, or even Asian American, community consciousness existed when I was younger because, from what I knew, my family was the only Vietnamese family in sight.

When I started college, my education became a safe haven for me, primarily through ethnic studies. For the first time, I had the opportunity to learn about my heritage in an institutional setting without feeling the need to cast aside my feelings and personal connections to the curriculum. Yet, when taking courses related to my heritage outside of the relative safety of ethnic studies, I was faced with biased professors, shocking images of death and destruction without warning, and again the reduction of my culture and history to a legacy of war. I was told by white professors that “Vietnamese people have no concept of democracy,” have “weird names,” and that “Boat People and their children walk these halls among us” as if we are some kind of curiosity. Being a first-generation college student and often the only Vietnamese student in the classroom, I did not know how to support myself or access the resources available to me.

Because of our lack of institutional support in both public and private educational systems, I started to work on community capacity building and social justice education with my peers in college and high school. Seeing the spirit and confidence that we gained from being able to learn and unlearn, love and resist, and be in community with each other has only strengthened my drive to empower minoritized communities and my desire to advocate for increased educational opportunities.

Today, I’m proud to recognize my refugee roots as a Vietnamese American and embrace my community wholeheartedly by advocating for the advancement of my Southeast Asian American peers. We cannot discount the critical importance of instilling a sense of worth and confidence in our students by tailoring our educational system to the needs of individual students and communities. In our schools, we need ethnic studies options for students to learn about themselves and those around them and curricula that represent our students well. We need accurate snapshots of our community created through data collection and storytelling. We need culturally sensitive educators, professionals qualified to assist our English language learners, college and career readiness programs, and a government that prioritizes our education.

For my family, our education has meant an opportunity to rebuild, to grow, and to share our stories. For Southeast Asian Americans, our education can help us overcome and honor our history, one replete with both struggle and triumph.

Luke Kertcher is SEARAC’s summer field and outreach intern. He is currently a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, where he is studying international relations with a minor in Asian American studies, as well as a graduate certification in human rights.

From Vietnam to Utica and back again: Reflecting on my refugee journey

There were no helicopters, boats, or military personnel when my mother and I left Vietnam for America. Instead, there were two white International Office of Migration bags, two suitcases of clothing, and two plane tickets from Saigon, Vietnam, to Syracuse, New York.

We resettled in Utica, New York, in 2001, joining my grandparents, who resettled in 1994. People always wonder why members of my family, especially my mother and I, resettled so late compared to the droves of Vietnamese that left Saigon immediately after 1975.

During what Americans remember as the “Vietnam War,” and the Vietnamese remember as the “American War,” my grandfather worked for the governments of the Republic of Vietnam and United States doing intelligence work, mainly mapping the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The rest of my family was engaged in democratic activism. After Saigon fell, my grandparents and eight of their children—with the exception of my mother, who was one year old—were sent to reeducation labor camps for nine years to atone for their wartime allegiances.

This experience would make them distrustful of all government and jade their relationship with politics and activism. Thus when my grandfather was offered the chance to resettle in the United States by the United Nations, he opted to wait. Part of him remained patriotic, patiently yearning for a reunited and democratic Vietnam, but the larger part of him was afraid of the unknown. He waited until one of his friends, resettled on the other side of the world, confirmed that the opportunity to continue building a life from the disjuncture of an old one was not too good to be true. He followed.

Utica, New York, was—and still is—an ideal place for refugee resettlement with its cheap housing, entry-level jobs, and welcoming ethos. I had a worldly upbringing amongst a diverse refugee population (more than 47 languages were spoken at my high school!) that has made me conscious of and curious about borders, mass displacement, and the urgency of refugee resettlement.

Growing up, I was aware that I fit the legal category of “refugee.” However, my family’s assimilationist attitudes borne of their past persecution prevented me from engaging with questions about what this distinction really meant and its historical relationship to Vietnam. Becoming a naturalized citizen in 2012 and imagining an American future without understanding my Vietnamese past did not offer any answers. These two modalities of citizenship and identity seemed mutually exclusive at the time.

I became deeply involved in activism during my high school years, working as an advocate for refugee and immigrant public education issues. However, it was not until college that I would think critically about my identity. Taking classes on migration, citizenship, and civil war prompted me to ask about my family’s fraught history in Vietnam, engage with Vietnamese literature, and return to my homeland for the first time in nearly a decade. In effect my activism began to complement my studies. Today my work centers on decriminalizing immigration, ending detention and deportation, keeping families together, and building sanctuaries.

I became deeply involved in activism during my high school years, working as an advocate for refugee and immigrant public education issues. However, it was not until college that I would think critically about my identity. Taking classes on migration, citizenship, and civil war prompted me to ask about my family’s fraught history in Vietnam, engage with Vietnamese literature, and return to my homeland for the first time in nearly a decade. In effect my activism began to complement my studies. Today my work centers on decriminalizing immigration, ending detention and deportation, keeping families together, and building sanctuaries.

The past wars in Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries cannot be extricated from contemporary discourse about refugee and immigration policy. Though U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia ended in the 1970s and 1980s, the diasporas it has created live on. Most precarious are the fates of former refugees who are currently being detained and deported to countries from which they fled decades ago. Their plight makes it clear that to be Southeast Asian in America means being the inheritor of intertwined and conflicting histories continually mediated and adjudicated through immigration policy decisions.

I am an immigration policy intern at SEARAC because I am optimistic that we can collectively build an American future that redeems the past for Southeast Asians and for all refugees and immigrants.

Trinh Q. Truong is a community activist and political theory student at Yale, where she is enrolled in a multidisciplinary human rights program. She is working at SEARAC this summer as an immigration policy intern.

Farewell from Mari

Last month I said goodbye to SEARAC, the organization where I lived and breathed a special brand of community-grounded policy work for six years. Though I came as a respectful ally and partner, I found family at SEARAC. What I learned from the community will fuel the remainder of my social justice career.

I came to SEARAC looking for a way to support refugee communities and work for immigrant justice. Unlike most of my colleagues, I do not come from a recent immigrant or refugee family—I grew up on a farm in rural Minnesota as a fifth-generation Norwegian American. It was in eighth grade that I first began to learn about the Southeast Asian American community. After responding to an ad in my local paper, I applied and was accepted to represent my district on the governor’s statewide Youth Advisory Council. Several Hmong American kids served on the council with me representing St. Paul, and I felt an odd kinship with them—I was quiet, and they were too, and I really wanted to know what they had to say.

In college in Minneapolis, I was driven to learn more. I volunteered in a learning circle with Hmong adults who taught me about Hmong language, story cloths, and their long history of migration, war, and displacement. I read everything I possibly could about Hmong communities globally. In 2001, I studied abroad in China with former SEARAC policy director Helly Lee. We immersed ourselves in ethnic minority studies and hiked to a remote Hmong village in Yunnan province together, where she read aloud letters from a family’s relatives in California that they hadn’t been able to decipher for years. As fellow Minnesotans, we kept in touch. Through Helly, I began working with the Lao American community at Legacies of War, advocating to clear unexploded bombs from Laos left over from the U.S. Secret War. Just before Helly left SEARAC in 2012, she convinced the executive director at the time to bring me on.

Six years later, I can say that I found my purpose in life at SEARAC—not from my meetings on the Hill or at the White House, which I never particularly enjoyed, but from the families I worked with who bravely fought their deportation orders, sometimes winning against all odds. My time as the immigration policy manager at SEARAC was intense and emotional, and I am forever changed by it. I want to thank these people in particular for inspiring me: Lundy Khoy, Many Uch, Rithy Yin, Tai Little, Touch and Puthy Hak, Jenny Srey, Montha Chum, and their beautiful families. They put their hearts and souls into fighting for their families and their communities, and I want to do everything I can to be useful as an ally in their movement.

Next fall I will start law school at Georgetown University Law Center, where I will be a Public Interest Law Scholar with a focus on immigration law. I hope to use my legal knowledge to push back on punitive criminal immigration policies that only perpetuate cycles of pain and trauma. Inspired by the success of the ReleaseMN8 campaign, I want to find innovative ways to keep families together despite those policies.

Thank you to the SEARAC community for being my home and my family for the last six years. I will remain a committed friend and co-conspirator in the years to come.

Mari Quenemoen is SEARAC’s former Director of Communications and Development. We are proud to have her as a member of the SEARAC family, and are excited to follow her career as she continues serving as a fierce advocate for family rights.